It seems simple: either a person’s seizures are controlled or they are not. However, what does it mean to have controlled seizures? To an Epilepsy Specialist, controlled seizures mean that the seizures have stopped. Uncontrolled seizures are ones which continue, even though the person has tried one (or many) medications. Surprisingly, many people come to their doctor, believing that their seizures are “under good control”. To that person, “good control” might mean that the seizures are “much better than they used to be.” However, even if the person is having one seizure per year, their seizures are uncontrolled.

Some people ask, “What is so important about having controlled seizures?” There are many reasons why a doctor will keep trying new medications (and other treatments) for uncontrolled seizures. The first is that seizures can cause falls, broken bones, and depending on the circumstances, burns. Second, though rare, is that seizures can cause death. This is called sudden unexplained death in epilepsy patients or SUDEP. SUDEP happens in people who have uncontrolled seizures.

Fifteen years ago, there were only a few medication options for treating epilepsy. In the past 15 years, many new medicines have been developed. In an era when many medications are available for treating seizures, how many should a person have tried before their seizures should be considered as uncontrolled? When should a person consider brain surgery for their seizures? What about devices, like the Vagus Nerve Stimulator (VNS), that treat seizures? And finally, when should a person be referred to an epilepsy center?

What the Data Show

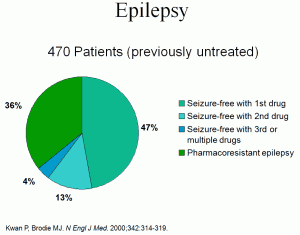

Surprisingly, only a few trials have attempted to answer the important question about when seizures should be considered as uncontrolled. The medical term for uncontrolled seizures is refractory: these terms mean the same thing. The most quoted study was performed by Kwan and Brodie in 2000 and published in the New England Journal of Medicine.1 This study, from the United Kingdom, included 525 people who were newly diagnosed with seizures. In the study, the people were followed for an average of five years. The results showed that the response to the first (or second) AED strongly predicted whether or not the person would ever respond to medication (see Figure 1).

In this study, 47 percent responded to the first AED, 13 percent were seizure-free on the second agent and only one percent achieved success with the third monotherapy. Three percent became seizure free on a combination of two medications. In other words, about two-thirds of people with epilepsy will respond to a reasonable number of medication trials, and one-third will not. Further, this information indicates that the determination of refractory can be made early in the treatment of the illness.

Why Should Someone be Referred to an Epilepsy Center?

The first step toward the best treatment is to identify the correct type of epilepsy. This comes as a surprise to many people with seizures: there are actually many kinds of epilepsy. Sometimes finding the right one is a challenge. An epilepsy center can help in making the correct diagnosis, especially if the episodes are vague or are “atypical” for seizures.

Once the diagnosis is made, the staff of the epilepsy center can better select an appropriate medication. The long list of possible medicines makes this a challenge as well. For instances, certain medicines may work well for some epilepsies, but may make other kinds of seizures worse. The best treatment for an individual takes all of this into account.

A referral to an epilepsy center can accomplish several things. First, if there is any question as to the type of epilepsy, video-EEG and/or newer neuroimaging techniques can help to make this clear. For a person with refractory partial seizures, epilepsy surgery may be offered as a treatment option. Finally, the epilepsy center may be involved in clinical trials for investigational medications or newer devices for the treatment of epilepsy. In short, the Epilepsy Center may have access to an even greater number of treatment options, providing more options to best treat the person’s seizures.

Treatment Options

Medication(s) are the first treatment a doctor will consider. The doctor needs to consider the kind of epilepsy, possible side effects, interactions between medications, and many other factors before they select a medication for a person with seizures. If two medications are tried, and the seizures do not stop, the doctor may refer the person to an Epilepsy Center for more testing. The testing might help to decide if a person would be able to have brain surgery or would do better with a device, like the VNS.

Just like with medications, brain surgery is not something that works for everyone. Medical testing (like MRI and EEG) can help the doctor to decide if a person might benefit from surgery. At the Epilepsy Center, more detailed testing like video-EEG, may make this clearer. A person who is a good candidate for brain surgery is someone who is very likely to benefit and very unlikely to have complications from the surgery. Only by talking with your doctor can you decide if surgery is right for you.

If a person has seizures that are not controlled with medication(s), and they will not benefit from brain surgery, there are other treatment options. One is a device called the VNS. The VNS has been available for 15 years. It is an electronic device, like a pacemaker, that sends small electrical impulses to the brain. These impulses help to decrease or stop seizures. The device is used in combination with medication.

For some people, the ketogenic diet helps to stop seizures. The diet has been “around” for many years. It is mainly used in children. In order to be on this diet, a person needs to work carefully with a dietician, who can help to design a meal plan that is best for that person.

Conclusions

The treatment of epilepsy has changed dramatically over the past decade, thanks mostly to the development of new medications, devices for epilepsy, and new surgical approaches. The growing list of treatments offers patients more options; however, it presents the neurologist with greater challenges. The best way to select the best therapy or a combination of therapies is not always clear. However, it has become clear that one-third of patients will not respond well to medications alone. This determination can be made early after diagnosis: if the first few medication trials do not produce seizure freedom and a tolerable side effect profile, the person’s seizures can be said to be refractory. It is at this point that a person should be referred to an epilepsy center.

Refrences

1. Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. New England Journal of Medicine 2000;342(5):314-9.